What Might It Take to Make Thinking a Crucial and Visible Aspect of Our Maker-Centered Classroom?

Thinking and Learning in a Maker-Centered Classroom online course co-instructor Julie Rains describes her self-imposed creativity challenge to foster interconnected episodes of learning and student thinking in her elementary media center makerspace.

Documentation: A Creativity Challenge?

When I started my new position as an Information Literacy Specialist four years ago, one tension that quickly surfaced was that of documentation--how could we document our thinking to encourage interconnected episodes of learning rather than one-off activities? Our elementary media center makerspace is a place that supports 27 sections, serves 620 students, and houses multiple community events before, during, and after school. The space itself is subdivided into three sections: a whole-class meeting zone, materials storage, and space for tinkering and collective participation. I wondered, how could evidence of the use of this space link to the creation of maker-centered learning opportunities schoolwide and the broader Agency by Design framework?

As a co-instructor of the Thinking and Learning in a Maker-Centered Classroom online course, I have a chance to hear from educators around the world. I know I am not alone, as these educators often share that they grapple with this same tension around documentation. Makerspaces are often community spaces, and classrooms have multiple demands, including that of physical and curricular space and time. Making thinking visible in our community space would take intentional planning and considerable time. As the primary facilitator of our media center space, I decided to approach this as a creativity challenge of my own, asking the question: What might it take to make thinking a crucial and visible aspect of our maker-centered classroom?

Developing a Curriculum and Environment to Support Thinking

My journey took several years and involved resources from many Project Zero (PZ) research projects. As one of PZ’s Principal Investigators, David Perkins, suggested in his book, Making Learning Whole, the first thing I considered was - what did I want students to get better at doing? Drawing upon the Teaching for Understanding framework, I generated throughlines that highlighted the intersections between the curriculum and the types of thinking we would consider. This process was a participatory undertaking and drew on the experiences of educators in neighboring districts and states, especially educators at Way Elementary School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

After much thought and tweaking, I settled on the following throughlines:

Kindergarten & Grade 1: How might the world work? We can question, tinker, and explore to discover new ideas about our world.

Grade 2: How might we find and use patterns to explain our world? We understand the use of patterns and thinking routines to explain our ideas.

Grade 3: How might diverse stories and ideas enrich our perspectives? We can understand diverse points of view by reading, listening, and interacting in a respeciful, non-judgmental way.

Grade 4: How might evidence and reasoning (or lack thereof) influence our thinking? We understand that we can change our minds based on evidence and reasoning or in the absence of evidence and reasoning.

Grade 5: How might we look closely, explore complexity and find opportunity to change our world? We can develop the sensitivity, capacity, and inclination to uncover complexity and solve problems.

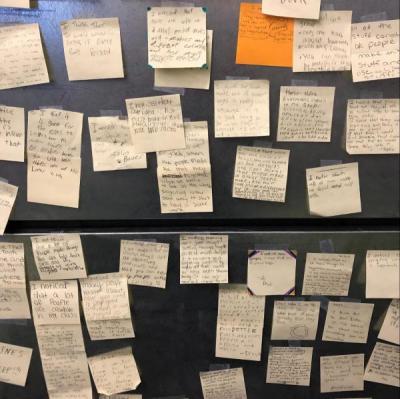

These questions and statements would serve as guideposts to our thinking and learning throughout the year. Since I saw students only once per week, for one hour each time, it would be of particular importance to keep these questions visible and reference them with intentionality throughout our time together. As a reminder to all learners, I posted each question and integrated them into our weekly Google slide lessons to frame our thinking. Linking to understanding goals based on the throughlines centralized our learning and enabled each class to revisit a common thread, increasing our depth of understanding and capacity to explore complexity at each iteration of the experience.

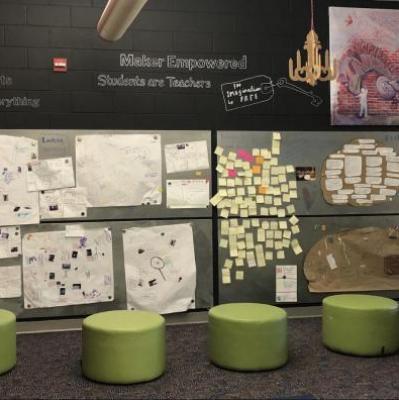

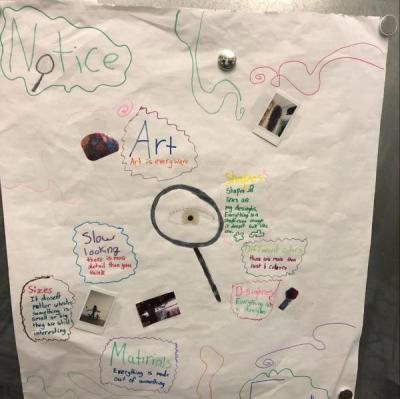

My next consideration was the physical environment. In his work on the Creating Cultures of Thinking project, PZ Principal Investigator Ron Ritchhart asks, Not only what are students learning, but what are they learning about learning? What messages are being sent? As I examined our own culture, especially through the lens of environment, I recognized a disconnect. In the media center, we literally had no wall space dedicated to student thinking. Bookshelves lined every wall. It was clear that we needed to reconfigure the space to support interactive spaces so that students could access and share their thinking. We also needed to balance that with the needs of our school library, making sure students had easy navigation to our book collection. Moreover, the large number of students posed a challenge of its own, necessitating the consideration of technology as a tool to document thinking. How would we have the physical space to post the thinking of 620 students? Somehow, we would need to balance our online and paper/pencil documentation with careful curation.

At around the same time, my district colleagues and I had the opportunity to visit Quaker Valley School District in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This district was heavily involved with the Agency by Design Pittsburgh cohort and they were incredibly generous in sharing their own processes. After several visits, I continued to be inspired by their use of a magnetic pegboard to house tools and their documentation of student thinking. I wondered, what if we used the magnetic pegboard to house both tools and documentation at the same time? That versatility would offer increased flexibility that would support our own media center needs. The magnetic aspect would allow for quick curation of ideas, without damaging student work.

After about a year of planning, a lot of amazing volunteers, and a bit of gumption, we were able to create designated spaces to support and document student thinking. Although still very much a process, these considerations have allowed us to develop a teaching and learning environment focused on thinking, and the documentation of that thinking.

At the onset of this undertaking, I wondered, what might it take to make thinking a crucial and visible aspect of our maker-centered classroom? There were many elements, including monetary support from our building and the local community, time allocated to redesign the space, and smaller elements, such as power tools to dismantle and reassemble bookshelves. Of all the factors, I believe the following elements were the most crucial to the development of our space:

- Reframing our existing curriculum to teach for understanding

- Shifting the physical environment to support student thinking

- A supportive school community and collaborative colleagues willing to brainstorm

- Intentional and interconnected lesson designs with time for student thinking and reflection

- Open-mindedness to take a risk and experiment with new ideas