Looking at student work takes time and needs to be scheduled into your practice. Include it as a component of class time if you are reflecting on learning with your students or as a part of professional development time if you are getting together with colleagues. Or, if for whatever reason, it isn’t feasible to work the practice into a professional development experience, set up more informal meetings with one or more colleagues to look together at student work whenever you can.

Looking at Student Work: Suggested Practices

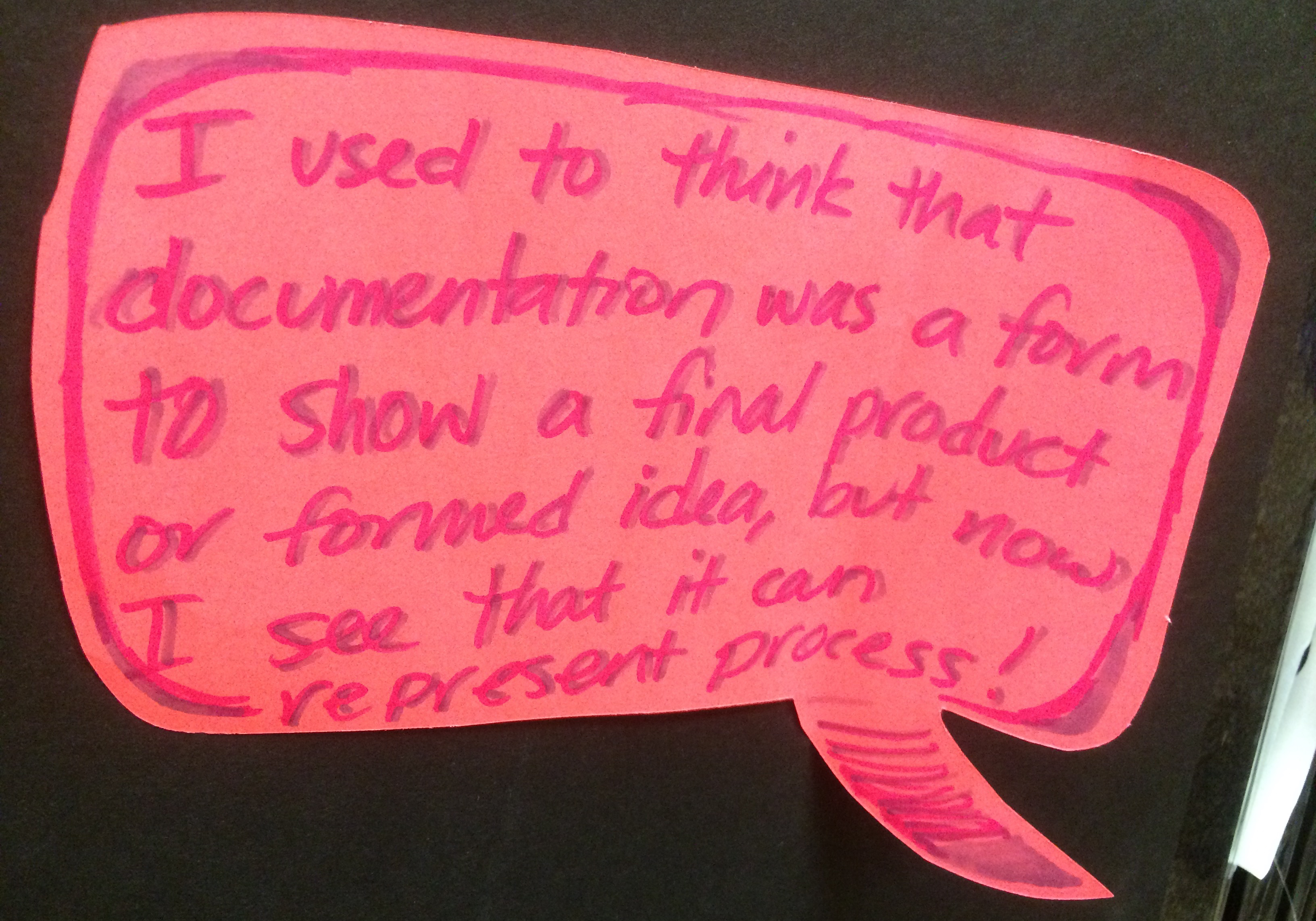

Before diving into the suggested practices for looking at student work, it is important to consider the broader practice of documentation.

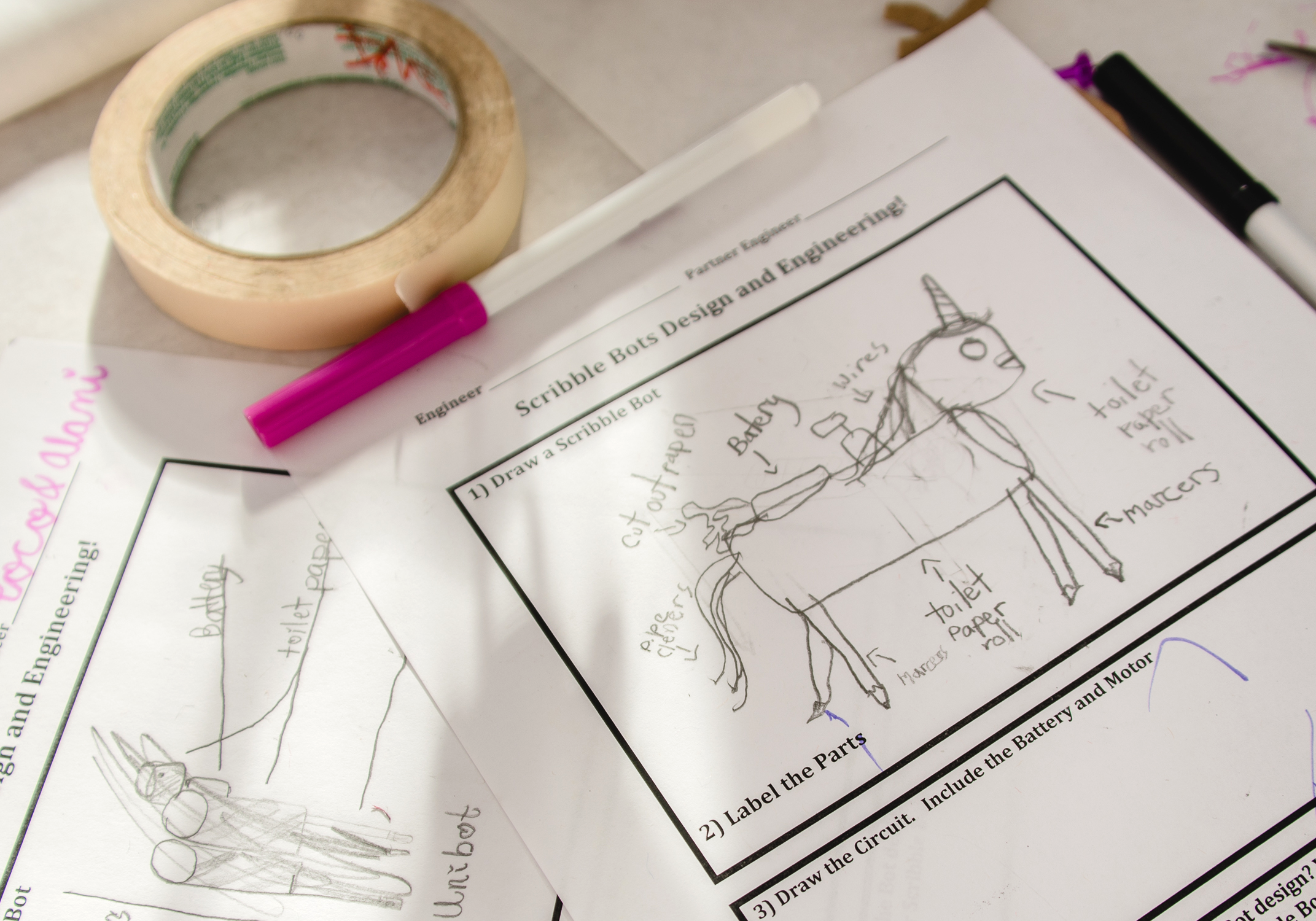

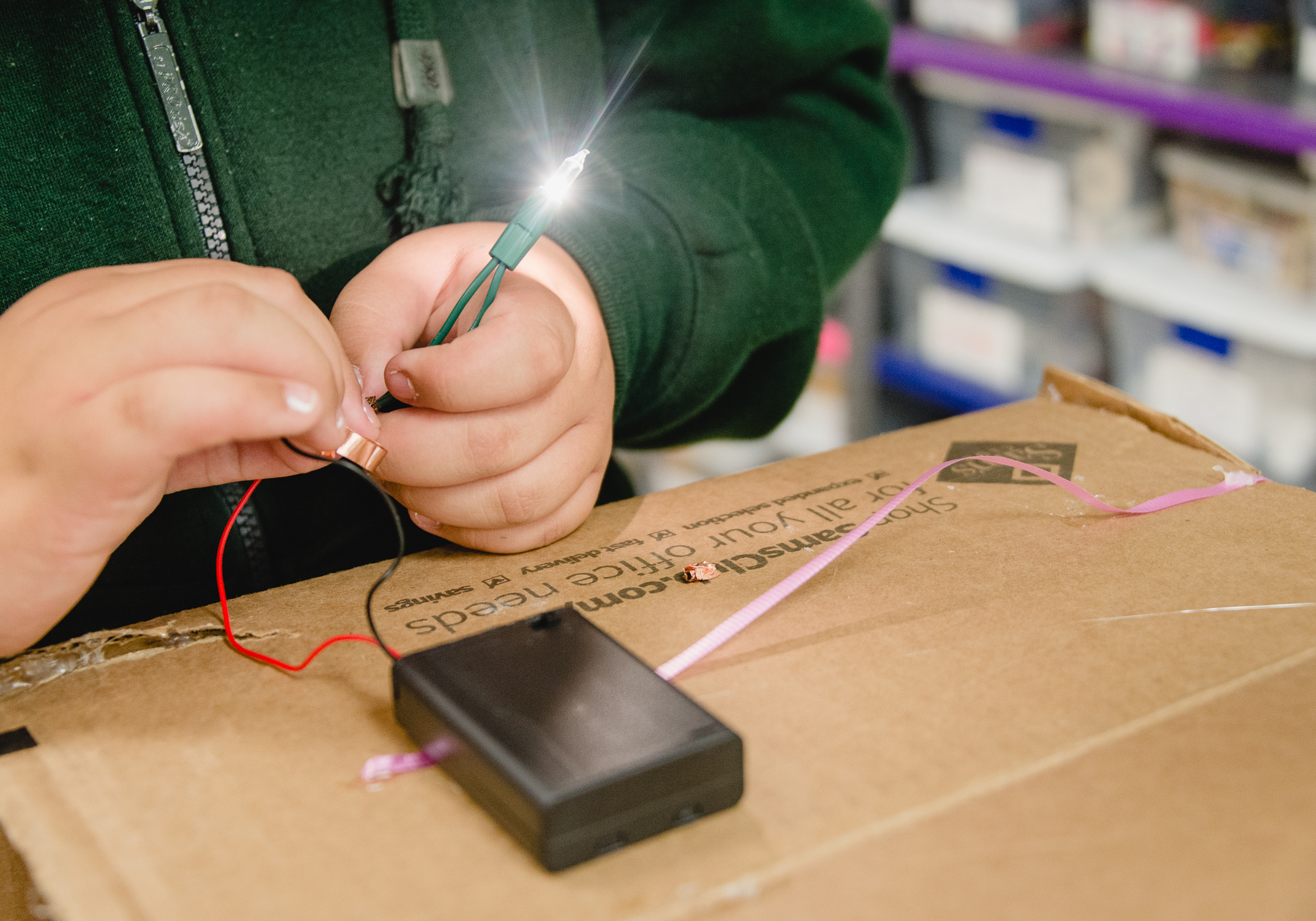

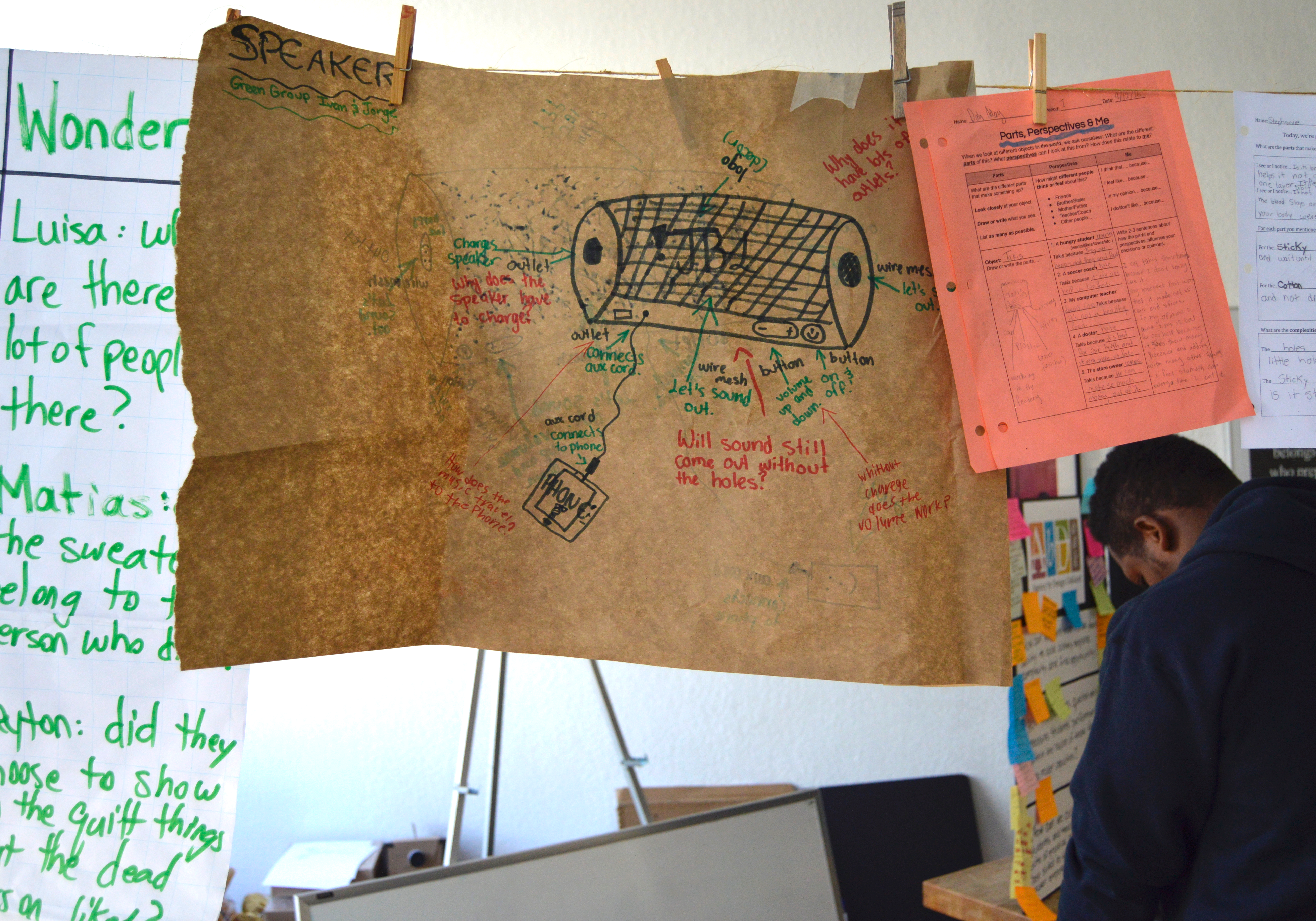

Documentation of student learning in a maker-centered environment can include documenting a vast and varied array of made products along with artifacts that capture the processes involved in the creation of those products.

These artifacts, also know as student work, represent learning that is often interdisciplinary in nature and that demonstrates the degree to which students have come to understand content knowledge and/or mastered specific skills and dispositions.

Collaboratively examining documentation of learning that includes both student’s products and processes offers an opportunity for educators and learners to reflect on learning and plan for next steps.

Documentation

The Agency by Design approach to documentation in the maker-centered classroom is grounded in the concepts presented in the book Visible Learners: Promoting Reggio-Inspired Approaches in All Schools (Visible Learners). Here, Project Zero researchers define documentation as “the practice of observing, recording, interpreting, and sharing through a variety of media the processes and products of learning in order to deepen and extend learning.” Throughout the Visible Learners text, the authors present a detailed approach to documentation, along with useful tools for educators. Below are two tenets of effective documentation, adopted from the Visible Learners text, that are particularly resonant with maker-centered learning.

Documentation is Purposeful and Intentional

Educators engaging in the process of documentation may feel overwhelmed when considering exactly which moments of student learning to record — and how. Rather than attempting to “record everything” educators should take an approach to documentation that is purposeful and intentional. To satisfy this approach, documentation should be driven by a guiding question. Once educators have a question in mind that they would like to explore they can observe and record moments of teaching and learning that are pertinent to that question.

Documentation is both Retrospective—and Prospective

Effective documentation is both retrospective and prospective. In other words, engaging in the process of documentation helps us understand what students have learned by making their thinking and learning visible, but it also functions as a tool to further support students as they continue their process of thinking and learning going forward.

Looking at Student Work

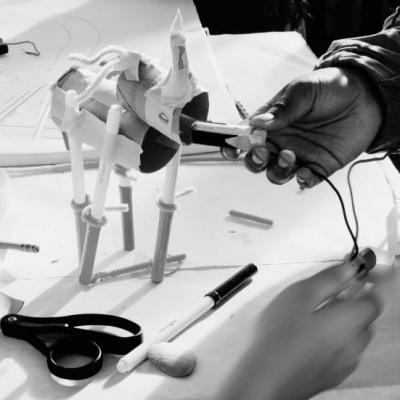

Educators from the AbD Oakland Cohort looking at student work

Suggested Practices for Looking at Maker-Centered Learning

Maker-centered learning can feel messy. In reality, it takes considerable time and planning to design and facilitate interdisciplinary, inquiry-driven, hands-on learning. The maker-centered classroom is lively and multidimensional. It can —understandably—be challenging to capture the process in these dynamic environments. Taking the time to interpret and then share the products and processes that occur in these spaces is a vital step towards assessing learning and planning forward. Below are some suggested practices for integrating a collaborative documentation practice.

Two tools that we have developed for documenting and assessing student learning in the maker-centered classroom include the Inquiry Cycle and the Observation Protocols for the Maker Capacities. A handout of the Agency by Design protocol for looking at student work can be found here.